Common Mallow/Malva neglecta/Tessa Thompson

Common Mallow

Malva neglecta

Tessa Thompson

You know, we’ve probably pulled more weeds than we could ever hope to plant.

It was an unusually hot morning for early spring, but my restoration crew did their best to swallow the feeling of impending climate doom and focus on clearing yet another overgrown patch of the local creek. I sat down beneath the shade of a downed willow to assess yet another rip in my work pants courtesy of the Himalayan blackberry that I could have sworn we removed last year. The orange flags that once marked new plantings now served as a type of grave marker for the California bunch grasses that didn’t survive weedageddon. Bummer, I thought, but then again, environmental restoration is not for those who are easily discouraged. My crew member was right, and ultimately, you will pull more weeds over the course of your career than you could ever hope to replace with native plants.

I absent mindedly plucked a funny looking weed from the soft dirt, twirling its root between my fingers, drowning out the sound of my team asking for the 5th time where to discard the growing pile of plant remains.

I had recently embarked on a personal quest to not only improve my ability to identify non-native plants, but also learn their stories. I had seen this plant before, growing in the cracks of the sidewalk, sometimes small and trailing, other times large and in charge, towering over the other weeds.

The flowers were small and delicate, but you could see the pink petals peeking out from behind the base of the leaf stalk. At first glance, I would have described the leaves as simply heart shaped, but a closer look revealed that they were lobed with small, wavy, toothed edges. The leaves and stems felt slightly fuzzy between my fingertips, and the long taproot told me why this plant was doing so well where others had failed.

Figure 1. Malva Leaf.

That mystery weed, as I would come to learn, is a member of the Malvaceae family. The Latin name is Malva neglecta. Malva is Latin for mallow, and neglecta is Latin for neglected or overlooked, or in this case, common. Common mallow is more often known as cheeseweed, a name derived from the shape of the fruiting heads, which, before fully ripening, resemble a wheel of cheese. When fully matured, the heads pop open, sending small kidney-shaped seeds in different directions.

Malva is prone to rusts, a plant pathogen that causes a fungal disease characterized by raised orange spots found on vegetation. Rusts spread via wind-dispersed spores and thrive in moist areas.

Malva is a pioneer species, meaning that it’s among the first to inhabit areas of recent disturbance due to its high adaptability, thriving across various climates. That long tap root I mentioned earlier enables Malva to thrive in the driest conditions, a strong hint about its nativity. Malva is native to regions such as North Africa, Southern Europe, and parts of Asia. It was introduced to Mexico by the Spanish and has long since escaped its garden captivity. Now it can be found in various parts of California from March to October, often dotting the ground after the first spring rains.

Figure 2. Pink flowers and hairy stems.

Where to begin with this powerhouse of a plant? Common mallow has a place in the kitchen and in traditional medicine. The leaves, which are high in vitamins A and C, are delicious when prepared fresh in a salad, boiled in soup, or battered and fried into a crunchy snack. The fruits have a flavor similar to a raw lima bean and are delicious in a stir-fry or soaked in a vinegar brine.

When cooked, the leaves produce a mucus-like texture that has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, making it a soothing remedy for sore throats, stomach upset, skin irritations, burns, and the prevention of stomach ulcers. This mucus-like texture is also good for thickening soups and stews!

Figure 3. Fruiting head and wilted flowers.

Malva species have been valued in traditional medicine for a long time, with archaeological evidence in Jordan indicating human use dating back to ancient times. In Lebanon, an infusion made from the flowers and leaves is used to treat arthritis and rheumatism. In Iran, the aerial parts, including leaves, flowers, and fruits, are used to soothe coughs, expel mucus, clear the lungs, reduce swelling, and acts as a gentle laxative. These medicinal properties come from the mucilage and flavonoids found in the vegetation.

As I uncover this plant's ever-growing list of medicinal and culinary properties, I can’t help but feel a sense of guilt. I had made what seems like a miracle plant my enemy and spent countless hours pulling it from restoration sites. Neglecta is a fitting name.

I find that “weed” is a designation that lacks creativity and strips many plants of their true identities, rendering them as blemishes on the landscape with no context. I encourage everyone who reads this essay to go out and learn the names of common weeds and reimagine your botanical relationships.

Literature

Mousavi, S. M., Hashemi, S. A., Behbudi, G., Mazraedoost, S., Omidifar, N., Gholami, A., Chiang, W. H., Babapoor, A., & Pynadathu Rumjit, N. (2021). A Review on Health Benefits of Malva sylvestris L. Nutritional Compounds for Metabolites, Antioxidants, and Anti-Inflammatory, Anticancer, and Antimicrobial Applications. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2021, 5548404. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5548404

Azab, A. (2017). Malva: Food, medicine and chemistry. European Chemical Bulletin, 6(7), 295-320.

Javed, A., Usman, M., Haider, S. M., Zafar, B., & Iftikhar, K. (2019). Potential of indigenous plants for skin healing and care. American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences (ASRJETS), 51(1), 192-211.

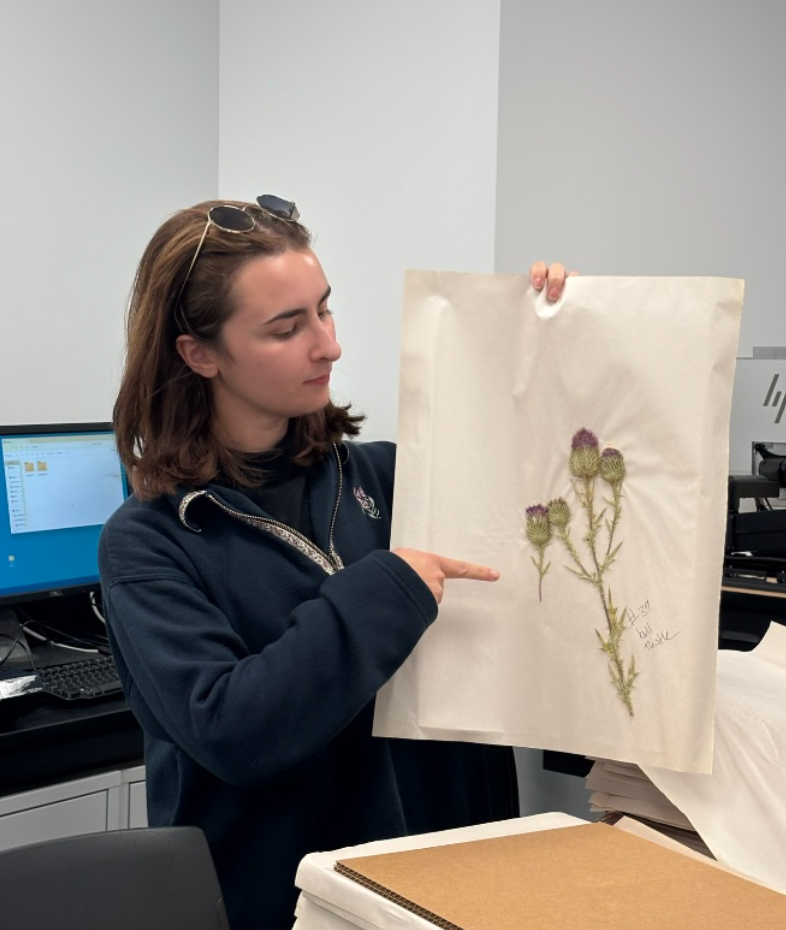

About the author

Tessa is a graduate student in cultural heritage and resource management, holding a BA in geography and environmental studies. Her current research focuses on ethnobotanical public interpretation and the management of biocultural resources in hopes of inspiring a new generation of responsible plant lovers.

The Society for Ethnobotany is open to researchers, practitioners, and enthusiasts of ethnobotany and economic botany.

The 2026 SEB Annual Meeting will take place in Montpellier, France, from May 31-June 4th!

If you have an interest in ethnobotany or economic botany you can become a member of the Society for Ethnobotany.

If you are a member of the Society for Ethnobotany and would like to contribute a Favorite Plant please contact Blair Orr, blairorr@ymail.com. (Note: ymail, not gmail.)